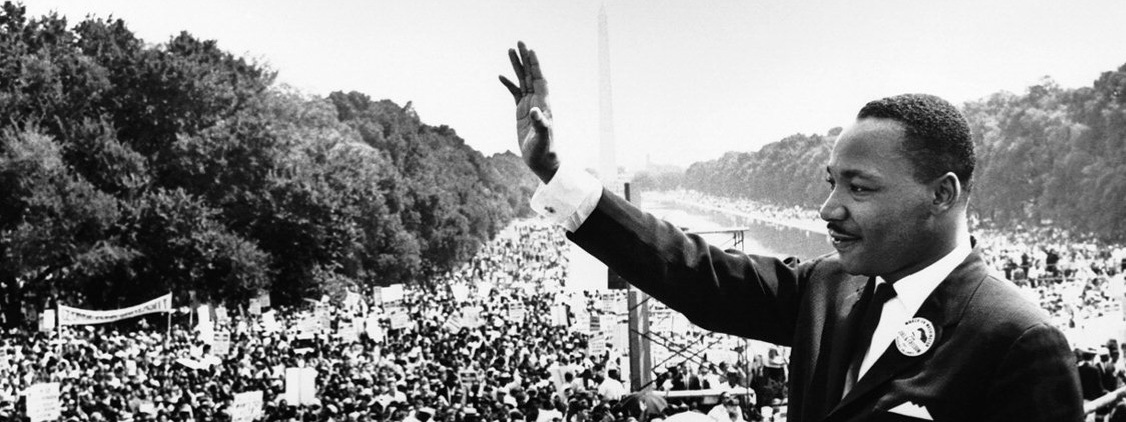

50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom: leaflet (2x pdf). Contact info@mlkjrway.org

A major connector street that runs between James Madison University (JMU) and the city's historic elite white neighborhood was named for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in an effort that originated in the African American community that started as the historic freed slave community of Newtown. The vision for the street came from Stan Maclin, President of the Harriet Tubman Cultural Center and he provided the focal point and sustained leadership under whose protection the movement grew and was brought to fruition.

The main work was achieved while the students were away with the only significant JMU full time faculty involvement being by an expert in African American labor history and the leadership of a historic African American Sorority. They both were taken by surprise by the initiative and asked to be included after it was underway. Even the opposition, who wanted to 'blame' JMU, had to admit it did not have a presence, with the subtle presence of the small pacifist Eastern Mennonite University being more significant. A multitude of leaders emerged under the umbrella created by Mr. Maclin, with the organic and diverse effort well represented by the sequence of speakers in favor in the hearing on August 13th 2013, where half a dozen people spoke before a member of the traditional political establishment spoke.

The potential of the event was recognized by (tenured, white, male) academics, but dynamics that could have swayed the directions of the effort were kept in check by writing and research from outside of traditional channels of power and prestige that emerged as a part of and stayed exclusively accountable to the community leadership that initiated the effort.

On Sunday, September 15, 2013, Stan Maclin was awarded the NAACP Image Award for his service to the community.

The following is a transcript of Mr. Maclin's account of the origin and outline of the street renaming effort provided shortly before his award.After living in Harrisonburg for maybe 12 years, I started thinking about all the efforts of promotion of diversity within the city. We have all these languages and nationalities, why isn't there more reflection of it in the infrastructure of the city? For example, city council, school board.

And then what really made me think was when they had finished the national memorial for Dr. King. It was beautiful, and I said wow, here it is -- the national capital honors and reflects the contributions of this African American to society. Isn't that a powerful statement. Why not Harrisonburg?

Why can't we have some reflection of diversity here? There is nothing here that reflects the diversity we boast about.

When I started looking at the permanent reflections of diversity in the city I wondered, where is the recognition of the contribution of African Americans? and I know the history of contribution exists here, because right here was Newtown, and Elon Rhodes, and the Lucy F. Simms Center.

On schools, nothing. All the symbols here reflect white culture. I had to dig deeper to find out how I could have a permanent reflection of diversity. So I said there needs to be a street named for Dr. King.

So I called Kai Degner, shared my idea with him, and he did not respond right back but he responded by email and said another council member is going to work with me on it.

At that time I was not thinking city wide. I was thinking Northeast.

There was Washington, Simms, Johnson-- one of the founders of Newtown, Ralph Sampson park, so what happened was I mentioned it. Said I'll test this idea at a NENA meeting, and I did some preliminary work knocking on doors. I had a flier , public hearings on a chance to make history in the Northeast and what happened was, I introduced it to a NENA meeting.

There was a big debate about Kelly street and should we even have a street in that area and I did not get the support it needed. But the president, Karen Thomas said she would work individually with me in an effort to try to get the street.

So I did bitty things in terms of testing and so forth. And I took sick, so for a whole year, 2012, I was out if it, out of circulation.

But I recovered at the start of January. I started my efforts again, Sarah Sampson I remember talking to and she said 'we don't need no street down here, we need to take it to the larger community.' So I talked to some more people and I said, I'll do that. February is coming, Black History Month. And so I will go to City Council and make my request known.

Well in January, we had an installation of officers with NENA. The Mayor was there and Charlie was there. I told them I am going to go to you with a street request and Mayor Byrd, of all people, suggest to me Vine street.. Of all people. And a light bulb went off, I said yes. Vine Street, wow.

I figured I can't go wrong with this because the Mayor said Vine Street. I said he is the mayor.

I said, well, ok, this is what I am going to do.

And Karen was there and she heard it, and that is what we did. February came around and it was Black History Month and so I said I gotta get together a delegation to support me to present this request. It was Karen Thomas, Brian Martin-Burkholder, Carlos Soriano. Feb 12.

When I made the request all they did was listen, then it was not until 2 months later that I got their attention.

I kept going back every time bringing speakers who would talk about the importance of naming a street for Dr. King.

[You were one of them.]

All they would do is listen to me.

Finally, in April, Kai Degner spoke up that Mr. [Maclin has been here several times and we should consider his request].

That is how I became Chairman. Council said get some people together under the auspices of Mr. Maclin and we got the first committee together.

Charlie had kind of been working with me together.

When we mentioned Vine Street there was a groundswell of people, and it was a no-brainer, there were 500 people, we could not do that.

So Charlie came to me and Karen Thomas with Cantrell, it came from Charlie. He for some reason tried to abort, but we stuck with it. We found there was no history. He sent me and Karen e-mails about Cantrell.

The spark to this effort was the monument in DC; shared it with several councilmen; inspired by the boasting of diversity, and the actual finishing of the national monument. If the nation can send a message to the other states, there is a reason why that is there. Why not here? symbolism is important.

This is the first contribution of a representation of diversity by African Americans here that I can see. Of course there was Lucy Simms, but that was done under segregation.

It was a calling.

Renaming a street for the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King has become a significant gesture across the United States and particularly in the South as an attempt to affirm a community's legacy of and aspirations for peace, civil rights, and justice, usually also affirming a significant African American history and community in that connection.

Such re-namings are usually accompanied by backlash and controversy as they force the community to grapple with its white supremacy. Often, the issue is complicated by claims of preserving history. Sometimes this history is racist, sometimes it is more benign, but its existence serves to divert discussion away from the contributions of a Martin Luther King, Jr. street renaming, away from the principles of peace, justice, and dignity for all, and away from uncovering and celebrating the African American part of our history that is too often invisible, not valued, or worse. Attempting to respectfully engage such renaming objections, to treat them as ignorance that is sincerely seeking dialogue and shared learning as opposed to taking them as deliberate affronts, can call upon people to devote substantial energy to painstakingly research an obscure historical figure or family relative. Bits of such 'history' pose the potential for either a cumbersome stumbling block or even a pernicious type of racist attack because some people who innocently have no clue as to who Dr. King was, what he meant to their neighbors and what he could mean to them can be drawn away from meaningful engagement. In the worst case, people with an ax to grind can purposely use such 'history' as a red herring to keep well-meaning people from investing their energy in more potentially profitable efforts to learn together. It can be used to give decision makers a way out of taking politically difficult stands and doing the right thing.

In the case of Harrisonburg, the search for historical excuses to avoid renaming Cantrell Avenue to Martin Luther King Way has given rise to half a dozen name origin stories. People with the skills to help could only move people from the wildly implausible to the implausible. The appeal of these themes projected onto random historical patterns, their number, and the ease with which re-naming opponents moved from one to the next revealed both the sentiment of those who oppose and that they could see their claims were wishful thinking.

In Harrisonburg, searches with this motive turned up empty for a reason. In brief, the original name of Cantrell Avenue was an error. The street came into being some time after 1885. It was initially called New Street. By May of 1903, it was called South Street. It was called South Street until at least March 14 of 1904, in a deed riddled with typing errors. On March 25 of 1904, it was called Cantrell Avenue in the society page. The next day it was called Cantral in a deed book, and Central in the Rockingham Register. On May 3, 1904 it appeared in the official Town Council Minutes as Cantral. In the Rockingham Register's coverage of those minutes, it appeared as Cantrell. The Rockingham Register council reports appear to have been prepared from draft minutes, but a petition by J. C. Staples may have also been available. Evidently, the reporter or editor corrected 'Cantral' to 'Cantrell,' something that looked less unusual and that happened to be a name in the news at the time. Central is a correct English word, was used for the street across South Main, which had been declared the East West divider by council in 1903, and when both were called South, Cantrell was called East South suggesting people did think of that up and over continuation. Either the street's name was the result of propagating an error, or people even at the time did not know for whom it was supposed to be named. See Andrew Jenner's summary of the data in its partially complete state that informed the vote at: Old South High.

The original name was just a place holder that ended up referring to whatever people cared to imagine. For example, the future Judge T. N. Haas could have been comfortable with the name, thinking of his counterpart, the Kentucky Democratic machine Judge James E. Cantrell. Before Cantrell became influential, he was an obscure Confederate officer who commented favorably on a terrorist who left his command to joined forces with William Quantrill: the character of whom Harrisonburg oral historians suggest ordinary people eventually thought.

In 1938, a novel was written that featured a fictionalize version of Quantrill, with the more streamlined spelling Cantrell. One can't help but speculate if the author might have gotten the idea for the streamlined spelling on a possible trip through the Shenandoah Valley in preparation for his Civil War novel. However, as we enter the time of living memory with the release of the 1940 John Wayne movie Dark Command based on the novel, it is easy to believe that the Kentucky virtuoso of Jim Crow constitutional law had already been forgotten and that kids throughout Harrisonburg were impressed that the name of one of their streets was in a John Wayne film, and that it went with a character who whipped the Yankees.

In 1978 the residential street was torn out to make way for a 4 lane commercial street, bearing the same name. On a modern map, the major connector street appears to be in sequence with the other connector to the south: Mosby, named for the Civil War's father of guerrilla warfare. At the point when these two became similar, the street was effectively named for a Hollywood movie villain based on Quantrill. Older residents give evidence that the pronunciation even changed from one resembling the pronunciation of Quantrill around Kansas City and Lawrence to the one in the film. At the start of this renaming process, multiple oral historians claimed that this was who Harrisonburg residents thought the street was named for, though there were some hints of the other tales that have since been traced and found implausible. Many people rightly doubted that a city would intentionally name a street for a terrorist war criminal. But by accident? Perhaps. The papers standardized the spelling to Cantrell. Another early variant was Cantral. If the latter is not a misspelling of Central but both refer to a person, the discrepancy suggests the person was known orally, not as someone about whom people read or to whom they wrote letters. While some Cantrells now live here and some passed through before the Civil War, there is no record of people with that name in the area in the decades around the renaming. Cantral looks like it should be pronounced the way the oldest Harrisonburg residents pronounce the name. In French, it seems that the 'Qu' in Quantrill (more commonly spelled Quantrell at the time he was active) should be pronounced as a hard 'c.' The street Harrisonburg has chosen to rename has no discernible naming for a positive historical figure.

The following arguments were made leading up to the vote:The major claim of history that bogs down most Martin Luther King, Jr. street namings does not hold back this renaming, except to the extent that people have personal fond memories of the busy 4 lane connector. If anything, the street has taken on an embarrassing connotation and should be renamed for that reason alone.

The argument of cost has also been addressed. Several strong examples have shown that city residents would not face costs beyond what they already face as a part of day to day life and that the city would also not face unusual costs. An early example of which at least one council member was aware was the coincidence in March 2013 of a problem-free street re-naming in Mesa Arizona that was similar in many details, except that it did not involved the name Martin Luther King. That council member was on a radio show on which the city manager prompted by a caller realized that a street renaming in which he took part was so uneventful that he had forgotten about it. Finally, a letter to the editor in the local paper pointed out that there had been no issues with the far more extensive switch to 911 street addressing in the 90s. In this case, all county roads had to adopt street names, changing every address in the county. Underlining how mundane the technicalities of street re-namings are, and how tenuous the connections to empty labels that were nonetheless names of places where people played while growing up, this vastly larger event did not even occur to anyone until after most of the debate had already played out, with all sides digging for all the arguments they could muster.

Thus, Harrisonburg's case is ideal for studying Martin Luther King naming dynamics because all the usual objections have been shown, sometimes unwittingly by the opposition themselves, to have no basis at all, leaving only the essence of the issue.

On the internet petition against renaming anything for Martin Luther King, every other signature with a comment is from a person who does not live in Harrisonburg. On the petition in favor of re-naming, four out of five signers with comments live in Harrisonburg. The comments against re-naming on social media, on petitions, and in conversations tend to be comments from people who are not aware that the cost arguments have been refuted, from people who state that they don't value what Dr. King stood for, and comments from people who claim they want to preserve history.Attempts to substantiate the history argument in the absence of a kernel of truth on which to draw have driven people to create revealing sentimental stories based on the tenuous scraps well intentioned researchers have helped them procure. The sentimental inventions tend to feature the little guy remembered by the nobleman. It is not that way now, and was not so at the start of the 20th century-- a time which was also the most blatantly racist time in the US 20th century. The person who really did speak to the needs behind the sentimental stories was Dr. King, if folks will let themselves see it.

Ready to support the change? Sign a :petition.

Cantrell Naming History